Foreign Insulators

by Marilyn Albers

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", September 1984, page 3

DON FIENE TAKES A TRIP TO THE

USSR

My column in the July '84 issue of Crown Jewels included a letter from Don

Fiene (Knoxville, TN), which said he would be going to Russia in June. When he

returned, he wrote me this delightful account of his travels, and, of course,

the inevitable insulator finds!

He made good pencil sketches of the insulators

for me, which is exactly what we need to make accurate drawings of them. But I

did not think these would print too well, so I tried to trace over them with

ink. Unfortunately, they don't look as good as his sketches did, but at least

you can get the general idea! He encouraged me to share his letter with you.

Dear Marilyn,

I returned from the USSR on June 23 (left NYC June 9). I led a

group of 40 people and had little time for really serious insulator searching.

Still, I picked up a few items. I never found the mother lode, though, and

that's all the more disappointing, as I was able to get the stuff I had through

customs with no hassle. I'll comment on what I found in the order they are

described on the enclosed sheets.

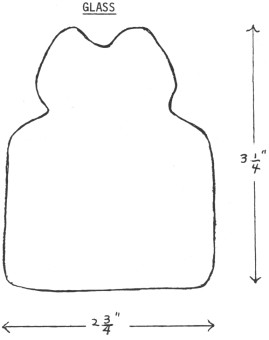

The only glass piece I obtained came from a

small village on the shore of Lake Baikal in far eastern Siberia. This lake is

the deepest, coldest, clearest, largest, oldest lake on the planet; it contains

20 percent of the earth's fresh water. It is located 3100 miles east of Moscow

and a few hundred miles north of Ulan Bator, the capital of Outer Mongolia. We traveled

there four days on the Trans-Siberian Express, which, so far as I could tell, was

electrified the entire distance. This means that I saw no fewer than 8 billion

insulators en route -- many of them quite exotic looking glass power types in

interesting shades of light blue and green. Most were porcelain, of course. We

made about 15 stops, most only 5 minutes, but five dragged on for 15 minutes. I

hiked into the train yards as far as I dared go, but never saw the first

insulator within stealing distance. I might mention, though, for the edification

of train buffs, that we passed through two smallish towns where part of the

train yards were given over to storage areas for steam locomotives. The only one

of these I saw seemed to have at least 100 engines. We saw no working steam

engines the entire trip. Probably these have all been replaced -- the last but

recently -- by electric and diesel. (But you never know; perhaps a few are still

hanging on in the far north.)

Our train let us off at Irkutsk, a major city at

the foot of Lake Baikal. I thought the place would have about fifty log cabins

and a grocery store, but it turned out to be a large and beautiful metropolis

with a population of 550,000. This is at the latitude of Labrador. The people

are quite handsome and very tall -- most unusual because Russians are short and

Orientals are short, yet, while Russians dominate, pure Mongols are common and

people of Eurasian mixture are to be seen everywhere. Whatever the secret of the

health and beauty of the Siberian people, they have had 300 years to develop

their own style. That's how long ago Irkutsk was founded! Now and then I could

see some similarities to Montana -- but Montana is just too new a place. It has no

cultural depth and no true sense of racial integration. And it's too far south.

We arrived at Irkutsk around noon, about 8 hours late. (Track repairs held us

up.) We were all very tired. Four days of light sleep, no bathing, and too much

booze had taken their toll. As one last digression, I think I'll mention that I

shared my four bed compartment with a Swede, a Russian worker who helped lay the

recent gas pipeline to Europe, and a remarkably beautiful young Russian woman

named Julia. (I forget the names of the other jerks.)

As soon as our late lunch

was over, around 3 p.m., I grabbed a "river tram" (hydrofoil boat) and

crossed the Angara River to a stop close to a railroad. I then walked the tracks

of the main Siberian line for two hours and failed to find one lousy insulator;

nor were there any interesting items on the nearby poles. All I had to show for

my walk were two types of date nail and four dates: three in the 1950's and

1971. Also, I noticed track maintenance was good; all the spikes were in all

their holes, and none were loose.

The next day we toured the lake by boat and

returned by bus. The bus stopped at a village. We were given an hour to stroll

through the place and check it out. All the houses were built of logs, but they

were large and comfortable-looking. Most had TV antennas. There was no running

water. Pumps were situated on the unpaved streets about every 300 yards. There

was electricity. Standard voltage in the USSR is 220. Lines coming into the

houses were tied to very small insulators. One such insulator I spotted in the

local store. I thought is was a fence insulator, as it measured only I"

high by 3/4" wide. But later I saw one on a house. I bought one as a

souvenir. It cost me 3 kopeks (about 4 cents). Most of the poles carried only

porcelain insulators (white); but there was some glass -- and some of it looked

heart-breakingly old, of a bubbly, translucent cobalt color. But the poles were

high and I was afraid to climb anyway. I wandered through several mini-dumps at

the edge of the village and found zero. Finally all the teenagers in the village

were let out of school and came marching up to us to demand souvenirs. I chatted

with about six of them, explained to them (and pointed out to them) what

insulators were, and said I wanted a glass one. I would pay. They all collected

foreign paper. So I agreed to pay one greenback. They ran off in various

directions. After ten minutes none had returned. By now the hour was up. The bus

was waiting. It was 1/2 mile away. It would look bad if the leader were to hold

the bus up (yet again). On the other hand, the bus would not leave without the

leader, either. Finally, I saw one of the little Siberian lads in the distance,

running like crazy. He came up to me and said that only one person had found an

insulator and he would be along soon. I almost went back to the bus, but finally

I saw the Messenger to Garcia raising dust. He handed me the insulator somewhat

sheepishly. The whole back of the skirt was broken out. But I gave him the

dollar anyway. I was relieved to learn later that the piece would stand by

itself. (If you blow on it hard, though, it falls over.) And that's it for

glass.

In Moscow I looked constantly for insulators. It is by no means a waste

of time to do so. Moscow is not New York. It is not all paved over. Greenery

abounds. Footpaths and alleys are everywhere. Once when I went to a bookstore I

noticed that in a kind of courtyard across the street some workmen were digging

trenches, perhaps for a water line. I poked among the piles of dirt and found

first of all (among hundreds of porcelain fragments) a common white porcelain

type (U-1654). It was near mint. (Though this is the same U-number as five

others I have, the shape and the dimensions, to say nothing of marking, are

sufficiently different so that I do not look upon it as a duplicate. Still, I

could possibly be talked out of it for an interesting piece of glass.) Poking

around further, I found two fairly large pieces from a sizeable brown insulator.

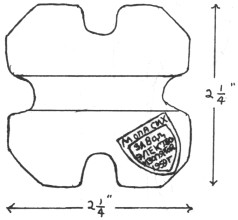

Finally, I picked up an elegant strain insulator of white porcelain, with a 1959

date. Unfortunately, it was wrapped about with a double length of 3/16"

iron wire that extended a foot or more from either end. It was imperative that

the wire be removed right then. (I had little hope of finding a hacksaw at the

hotel.) Of course I was running very late, but I walked far back into the

courtyard area, looking for the tools I needed. Finally someone showed me the

trailer where the workmen kept their tools. I went up to one of the workers, who

was eating his lunch, and explained that I was a weird American who collected

insulators and I had to have a hacksaw pronto! He and his buddy had had no truck

with Americans before. While they sawed my wire (which did not yield easily)

they sought my views about the Olympic Games and world peace. And we all agreed

that the Games should be free of politics.

We arrived at Leningrad (flying the

whole incredible distance from Irkutsk) around 8 p.m. But it was hours before we

were ready to hit the streets. And of course we were all hideously fatigued as

usual. Our hotel was way out on the outskirts of town, on the Finnish Gulf. It

was a nice new hotel, built for the 1980 Olympics. Around 11 p.m. I walked out

onto the esplanade at the rear of the hotel. I had the idea that I would just

sort of sit on the sea wall, sip my beer, and savor the midnight sun -- and then

split for my room and sleep. But as I sat there surveying the scene, I noticed

that to the west of the hotel a vast construction project was in progress. I

detected a faint aroma of insulators in the offshore breeze. So I set off for

the west and hoped for the best.

The construction project was a vast effort to

supply sewers many years late for the hotels and new housing in the area. Twenty

feet separated the top of the highest dune from the bottom of the lowest trench.

It was all land-fill. I cheerfully explored fifty years of Leningrad Middens. I

found pieces of large power insulators 3 feet long and 1 foot wide; and little

fuses one inch around (one of which I took home). There were plenty of destroyed

TV sets. Lots of metal, wire, glass. I picked up numerous bottles, finally kept

three smallish ones that I stuffed in my pockets. They were perhaps 20-30 years

old, but had the shape of American bottles maybe 70 years old. As I walked

along, now dropping down into a trench, now scouting the shore right into the

water of the Baltic Sea, I observed one thing above all: in all that breadth and

depth there was almost no plastic. Not a Clorox or an All bottle anywhere. Is

that good or bad? Who knows? The entire USSR seems to have avoided the plastic

age. For them, it's all heavy, expensive glass. Avoiding plastic means no Scotch

tape, either. Soviet offices use big pots of glue, usually hot, in which a brush

permanently swims. Actually, something like Scotch tape does exist, but it is

not common. Neither are staples common. The most common implement for fixing two

or three pieces of paper together is a common straight pin. As if that were not

enough of a problem, from the American point of view, there is an apparently

permanent paper shortage in the USSR. Often packages are wrapped for mailing in

thin cloth rather than paper. And in public toilets, including those on trains,

paper is almost never provided or else it gets stolen. For an American in the

USSR all of this is more or less quaint -- a kind of curious excursion into the

past. For many Russians it is an irritation. They see no virtue in being quaint.

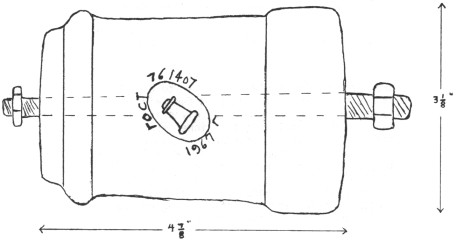

But in all that land-fill mess I found only one insulator (see No. 3) -- a type

of strain insulator used in anchoring trolley line support wires to poles and

buildings. It is of dingy white porcelain, shaped like a beer mug without handle

or bottom and with walls 1/2" thick. The inside is filled with gray cement;

protruding from each end in the center is a bolt and nut. I found this heavy

item right around midnight; the sun was just below the horizon and the sky was

very light. It was the longest day of the year -- June 21. I kept on with my dump

picking for another hour or so. I finally picked up a green enameled metal

chamber pot to hold my loot in.

By the time we went through customs at the

airport two days later, I had added three Russian Pepsi Cola bottles to my potty

full of glass and crockery. The customs inspector hardly knew what to make of my

garbage. When he learned that I actually collect insulators, he rolled his eyes

in amazement. He poked around in my suitcase and found a Soviet Army belt and

Navy belt which he confiscated. This seemed to make him happy. He waved me on

through with all my glass, ceramic and iron junk.

I was vastly disappointed that

I found so few insulators in the USSR. I want to go back as soon as possible and

see if I can't score a big find. At least I know I will have a good chance of

getting the things through customs. When I brought out the earlier batch of 25

pieces (on another trip), my baggage was not searched, so I didn't know if I was

getting away with anything or not.

Hope you found some good stuff at the

National.

Sincerely,

Don Fiene

|

Similar to CD 540 though smaller.

My piece is broken

after the 7-. Obviously this is the date. Opposite on back is the mold no. 50.

|

PORCELAIN

|

Mark on top of white porcelain U-1654 type. Lt. brown underglaze,

almost impossible to read. Seems to be symbols rather than letters. |

|

White

Porcelain Strain

Insulator Mark is stamped in black on unglazed bottom. The top

letters are partly illegible -- don't make sense -- probably an abbreviation.

The

next four lines mean:

|

Electro- |

1. |

Factory |

|

Insulator |

2. |

Electro- |

|

Factory |

3. |

Insulator |

|

4. |

1959-year |

|

White porcelain insulator with brownish gray tint. It was

used at the point where support wires for overhead trolley car and trolley bus

lines came in to a pole or building. The underglaze marking is in dark green.

The letters are probably an abbreviation for "Government Transport".

The insulator's interior is filled with gray cement.

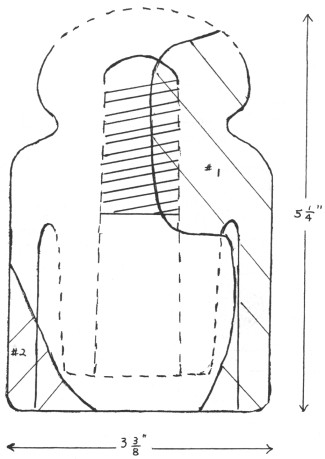

Brown porcelain insulator

similar to U-1278. It has been reconstructed from two fairly large fragments.

Fragment #1 gives virtually full height, shows height of inner skirt and

indicates extent of threaded hole, which (even though the top of the insulator

is missing) extends up so far that there is almost certainly no cable groove in

the top. The diameter of the threads, inner skirt and length of skirt are

estimated. Fragment #2 contains 1/3 of the base circle.

|